WHAT IS ROMAN ARCHITECTURE

Roman Architecture continued the legacy left by Greek architects and the established architectural orders, especially the Corinthian. The Romans were also innovators and they combined new construction techniques and materials with creative design to produce a whole range of brand new architectural structures. Typical innovative Roman buildings included the basilica, triumphal arch, monumental aqueduct, amphitheatre, and residential housing block.

Many of the Roman architectural innovations were a response to the changing practical needs of Roman society, and these projects were all backed by a state apparatus which funded, organised, and spread them around the Roman world, guaranteeing their permanence so that many of these great edifices survive to the present day.

The Architectural Orders

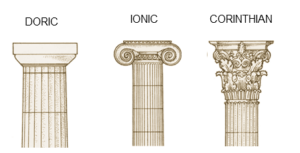

Roman architects continued to follow the guidelines established by the classical orders the Greeks had first shaped: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The Corinthian was particularly favoured and many Roman buildings, even into Late Antiquity, would have a particularly Greek look to them. The Romans did, however, add their own ideas and their version of the Corinthian capital became much more decorative, as did the cornice – see, for example, the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome (203 CE). The Romans also created the composite capital which mixed the volute of the Ionic order with the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian. The Tuscan column was another adaptation of a traditional idea which was a form of Doric column but with a smaller capital, more slender shaft without flutes, and a moulded base. The Tuscan column (as it came to be known in the Renaissance period) was especially used in domestic architecture such as peristyles and verandahs. The Romans also favoured monolithic columns rather than the Greek approach of using several drums stacked on top of each other.

In addition, columns continued to be used even when they were no longer structurally necessary. This was to give buildings a traditional and familiar look, for example the front of the Pantheon (c. 125 CE) in Rome. Columns could be detached from the building yet remain attached to the façade at the base and entablature (free-standing columns); see, for example, Hadrian’s Library in Athens (132 CE). Finally, columns could become a part of the wall itself (engaged columns) and function as pure decoration, for example, the upper floors of the Colosseum exterior (last quarter 1st century CE).

Greek influence is also evidenced in the fact that late Republican innovation, such as the basilica and bath buildings, usually occurred first in the south of Italy in Campania (see especially Pompeii) which was closer to the long-established Greek colonies of Magna Graecia. It was from here that we have the oldest surviving dome building, the frigidarium (cold room) of the Stabian Baths at Pompeii (2nd century BCE). As with many other areas, the Romans took an idea and pushed it to its maximum possibility, and the huge imperial bath complexes incorporated soaring arches, arches springing directly from column capitals, and domes which spanned seemingly impossible distances.

The Augustan period saw a surge in building activity, innovation in design, and extravagant use of marble, symptoms of a Rome that was beginning to flex its muscles and with an increased confidence break away from the rigid tradition of earlier civilizations. This was also the time when increased imperial patronage allowed for ever bigger and more impressive building projects to be undertaken, not only in Rome itself but across the Empire, where buildings became propaganda for the might and perceived cultural superiority of the Roman world.

As the Empire expanded, ideas and even craftsmen became integrated into the Roman architectural industry, often following their familiar materials like marble to the sites of construction. The evidence of eastern influence can be seen in such features as papyrus leaves in capitals, sculptured pedestals, street colonnades, and the nymphaeum (ornamental fountain).

Materials & Techniques

The first all-marble building was the Temple of Jupiter Stator in Rome (146 BCE), but it was not until the Empire that the use of marble became more widespread and the stone of choice for the most impressive state-funded building projects. The most commonly used from Italy was Carrara (Luna) marble from Tuscany (see, for example, the 30 BCE Temple of Apollo on the Palatine). Marble was also readily available from across the empire; especially esteemed were the Parian marble of Paros in the Cyclades and Pentelic from Athens. Coloured varieties were also much favoured by Roman architects, for example, yellow Numidian marble from North Africa, purple Phyrgian from central Turkey, red porphyry from Egypt, and green-veined Carystian marble from Euboea. Foreign marble was, though, mainly reserved for use in columns and, due to the costs of transportation, imperial projects.

Besides marble, travertine white limestone was also made available from quarries near Tivoli, and its favourability towards precise carving and inherent load-bearing strength made it a favourite substitute for marble amongst Roman architects from the 1st century BCE. It was especially used for paving, door and window frames, and steps.

The Romans did not invent lime mortar but they were the first to see the full possibilities of using it to produce concrete. Concrete rubble had usually been reserved for use as a filler material but Roman architects realised that the material could support great weight and could, therefore, with a little imagination, be used to help span space and create a whole new set of building opportunities. They called this material opus caementicium from the stone aggregate (caementa) which was mixed with the lime mortar. The material had a thick consistency when prepared and so was laid not poured like modern concrete. The first documented evidence of its use is from 3rd century BCE Cosa and its first use in Rome seems to have been a 2nd century BCE warehouse. Also in the 2nd century BCE it was discovered that by using pozzolana (concrete made using volcanic sand, pulvis puteolanus), which had a high silica content, the concrete could set under water and was even stronger than normal concrete. By the 1st century BCE its use seems widespread in foundations, walls, and vaults. Perhaps the best example of its possibilities in construction is the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina.In addition to the structural possibilities offered by concrete, the material was also a lot cheaper than solid stone and could be given a more presentable façade using stucco, marble veneer, or another relatively cheap material: fired brick or terracotta. Sun-dried mud bricks had been used for centuries and continued to be used for more modest projects up to the 1st century CE, but fired bricks had the advantage of durability and could be carved just like stone to resemble such standard architectural features as capitals and dentils.

Bricks were typically 59 cm square and 2.5-5 cm thick. Uncut they were used in roofing and drains, but for other uses they were usually cut into 18 triangles. There were also circular bricks, typically cut into quarters, which were used for columns. Bricks could also be used in domes such as that of the Temple of Asklepios Soter at Pergamon and even became a decorative feature themselves by using different coloured bricks (usually yellow and orange) and laid to create patterns.

Stucco was used to face brick walls and could be carved, like bricks could be, to reproduce the architectural decorations previously rendered only in stone. The stucco was made from a mix of sand, gypsum, and even marble dust in the best quality material.

Volcanic tufa and pumice were used in domes because of their light weight as in, for example, the Pantheon. Basalt was often used for paving and roads, laid as polygonal blocks, and Egyptian grey and pink granite was popular for obelisks and columns. Finally, terracotta was also used for moulded ornamentation on buildings and became a common embellishment of private homes and tombs.

Roman Architects

In the Roman world the credit for buildings was largely placed at the feet of the person who conceived and paid for the project rather than the architect who oversaw the realisation of it; therefore, he often remains anonymous. Those architects employed for specific projects by the emperor are better known. We know of Trajan’s favoured architect, Apollodorus of Damascus, famed for his skills in bridge building, for example, and who was responsible for, amongst other projects, Trajan’s Forum and Baths in Rome (104-9 CE). Severus and Celer were the architects responsible for the fantastic sounding revolving roof of Nero’s Golden House. In general, architects supervised whilst it was contractors (redemptores) who actually carried out the project based on the architect’s measured drawings.

Certainly, the most famous Roman architect is Vitruvius, principally because his On Architecture, a 10-volume study of architecture, has survived intact. We do not actually know much about his own work – only a basilica he constructed in Fano and that he did work for Julius Caesar and Augustus. On Architecture covers all facets of architecture, types of building, advice for would-be architects, and much more besides. One interesting point about the work is that it reveals that the ancient architect was expected to have many skills which nowadays would be separated into different specialisations. Vitruvius also encapsulated the essential ethos of Roman architecture: ‘All buildings must be executed in such a way as to take account of durability, utility and beauty.’ (On Architecture, Book I, Ch. III)

Key Roman Buildings

Aqueducts & Bridges – These sometimes massive structures, with single, double, or triple tiers of arches, were designed to carry fresh water to urban centres from sources sometimes many kilometres away. The earliest in Rome was the Aqua Appia (312 BCE), but the most impressive example is undoubtedly the Pont du Gard near Nimes (c. 14 CE). Roman bridges could make similar use of the arch to span rivers and ravines. Constructed with a flat wooden superstructure over stone piers or arches, examples still survive today. One of the best preserved is the granite Tagus Bridge at Alcantara (106 CE) which has arches spanning over 30 metres.

Basilicas – The basilica was adopted by the Christian church but was conceived by the Romans as a place for any large gathering, with the most common use being law courts. They were usually built along one side of the forum, the city’s marketplace, which was enclosed on all sides by colonnades. The basilica’s long hall and roof were supported by columns and piers on all sides. The columns created a central nave flanked on all sides by an aisle. A gallery ran around the first floor and later there was an apse at one or both ends. A typical example is the Severan Basilica at Lepcis Magna (216 CE).

Baths – Roman baths display the typical Roman ability for creating breath-taking interior space using arches, domes, vaults, and buttresses. The largest of these often huge complexes were built symmetrically along a single axis and included pools, cold and hot rooms, fountains, libraries, under-floor heating, and sometimes inter-wall heating through terracotta piping. Their exteriors were usually plain, but within they were often sumptuous with the lavish use of columns, marble, statues and mosaics. One of the finest and certainly best surviving examples is the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (completed 216 CE).

Private Homes – Perhaps more famous for their richly decorated interior walls using fresco and stucco, Roman private residences could also enchant with atrium, peristyles, gardens and fountains, all ordered in harmonious symmetry. For a typical example, see the House of the Vettii at Pompeii (1st century BCE – 79 CE).

Even more innovative, though, were the large apartment blocks (insula) for the less well-off city-dwellers. These were constructed using brick, concrete, and wood, sometimes had balconies, and there were often shops on the ground floor street front. Appearing as early as the 3rd century BCE, by the 1st century BCE examples could have 12 stories, but state-imposed height restrictions resulted in buildings averaging four to five stories (at least at the front side as there were no such restrictions for the rear of the building). Some of the very few surviving examples may be seen at Ostia.

Temples – The Roman temple was a combination of the Etruscan and Greek models with an inner cella at the rear of the building surrounded by columns and placed on a raised platform (up to 3.5 metres high) with a stepped entrance and columned porch, the focal point of the building (in contrast to Greek temples where all four sides could be equally important in the urban landscape). Surviving practically complete and a typical example is the Maison Carrée at Nimes (16 BCE). Temples were usually rectangular but could take other forms such as circular or polygonal, for example, the temple of Venus at Baalbeck (2nd-3rd century CE).

Theatres & Amphitheatres – The Roman theatre was of course inspired by the Greek version, but the orchestra was made semicircular and the whole made using stone. The Romans also added a highly decorative stage building (scaenae frons) which incorporated different levels of columns, projections, pediments, and statues such as is found in the theatre at Orange (27 BCE – 14 CE). A similar approach was taken with façades of libraries – see, for example, the Celsus Library in Ephesus (2nd century CE). Theatres also display the Roman passion for enclosing spaces, especially as they were often (partially or completely) roofed in wood or employed canvas awnings.

The fully enclosed amphitheatre was a particular favourite of the Romans. The Colosseum is the largest and most famous, and it is a typical example copied throughout the empire: a highly decorative exterior, seats set over a network of barrel vaults, and underground rooms below the arena floor to hide people, animals and props until they were needed in the spectacles.

Triumphal Arches – The triumphal arch, with a single, double, or triple entrance, had no practical function other than to commemorate in sculpture and inscription significant events such as military victories. Early examples stood over thoroughfares – the earliest being the two arches set up by L.Stertinius in Rome (196 BCE) – but later examples were often protected by steps. Topped by a bronze four-horse chariot, they became imposing stone monuments to Roman vanity. The Arch of Constantine (c. 315 CE) in Rome is the largest surviving example and is perhaps the last great monument of Imperial Rome.

Walls – Aside from the famous military structures such as the Antonine and Hadrian’s Wall (c. 142 CE and c. 122 CE respectively), even more modest Roman walls offer a surprising number of variations. The width of Roman walls could also vary tremendously from the thinnest at 18 cm to a massive 6 m thick. Rarely were marble and fine stone blocks used as this was too expensive. Large square blocks were used to create ashlar masonry walls, that is, close-fitting blocks without any use of mortar. Much more common was the use of brick (usually triangular shaped and set with mortar) and small stones facing a concrete mix core. The bricks and stones could be arranged in various ways:

opus incertum – first appeared in the 3rd century BCE and used small irregular chunks of stone smoothed on one side.

opus reticulatum – from the 2nd century BCE and used pyramid-shaped chunks with 6-12 cm square base and height of 8-14 cm. The stone was set with the base facing outwards and laid in diagonal arrangements.

opus mixtum – common from the 1st century CE, this was a combination of opus reticulatum with a layer (course) of horizontal brick every fourth course and at the edges of the wall.

opus testaceum – common from the 1st century CE and used courses of brick only.

opus vittatum – used an alternative course of brick with two courses of tufa blocks with a rectangular side facing outwards and diminishing in size towards the inner surface. It was especially popular from the 4th century CE across the Empire.

Despite the decorative effect of these various arrangements of stone and brick, most walls were actually covered both inside and out with white plaster stucco for protection against heat and rain for the outside and to provide a smooth surface for fine decorative wall painting on the inside.

Conclusion

Roman architecture, then, has provided us with magnificent structures that have, quite literally, stood the test of time. By combining a wide range of materials with daring designs, the Romans were able to push the boundaries of physics and turn architecture into an art form. The result was that architecture became an imperial tool to demonstrate to the world that Rome was culturally superior because only she had the wealth, skills, and audacity to produce such edifices. Even more significantly, the Roman use of concrete, brick, and arches twinned with building designs like the amphitheatre and basilica would immeasurably influence all following western architecture right up to the present day.